My Sherry Amour

It was International Sherry Week recently, so what better time to taste (drink) my way through a cross section of some of the best wines that Jérez has to offer?

I'm not sure if many people are aware of how Sherry is made, or the range of styles available, so I thought I'd provide a bit of a background to the topic. Unfortunately, there isn't really a way to cover the topic concisely so I beg your indulgence!

Palomino (Listán) is the main grape variety used for making sherry, its neutral, low-acid wines are perfect as the base for fortification and maturation. It covers approximately 95% of the vineyard acreage in Jérez and is particularly well suited to the chalky, limestone-rich albariza soil that allows the vine roots to penetrate deeply in a search of moisture beneath its baked crust. Albariza soils are concentrated on the slopes of Jérez Superior, a sub-region between Sanlúcar de Barrameda and the Guadelete River. 80% of the appellation’s vineyards are located in Jérez Superior, and most vineyards are located within the area of Jérez de la Frontera.

Moscatel and Pedro Ximénez are predominantly used for sweetening Sherry. Moscatel is mainly planted in the sandy arenas soils near Chipiona. Plantings of Pedro Ximénez have diminished so much that the Consejo Regulador has granted special dispensation allowing producers to import Pedro Ximénez must from the nearby Montilla-Moriles DO. Both varieties generally undergo the soleo process for a period of one to three weeks, in which grape bunches are sun dried prior to pressing. Palomino may also be “sunned”, but rarely for longer than 24 hours and often not at all.

Harvested in early September, Palomino is pressed quickly after picking as it is prone to oxidation. A maximum 72.5 litres of juice may be pressed from 100kg of grapes; any additional amount is relegated to the production of non-classified wines or distillate. Pressing is is a key factor in the sherry making process, as different compositions of must are obtained according to the amount of pressure applied. The pressed must (mosto de yema) is divided into three levels of quality. That referred to as "primera yema" must (approximately 65% of the total volume) is obtained with a pressure of up to 2 kg/cm2; the "segunda yema" must (approximately 23%) is obtained with a pressure of up to 4 kg/cm2 and, finally, that known as "mosto prensa" is produced by applying a pressure of over 6 kg/cm2. The particular characteristics of primera yema must make it suitable for biological ageing, whereas segunda yema must, with its firmer structure extracted from the grape solids, is used to produce wines better suited to oxidative or physico-chemical ageing. Mosto prensa is often used for distillation or to make Sherry vinegar.

Before fermentation commences, the must is usually acidified and sulphured, then allowed to settle. Traditionally, producers adhered Gypsum (yeso) to the grapes prior to pressing, which aided clarification and, when combined with cream of tartar, produced tartaric acid. Today, most producers add tartaric acid directly and utilise a system of racking (desfangado) to clarify the must before fermentation begins.

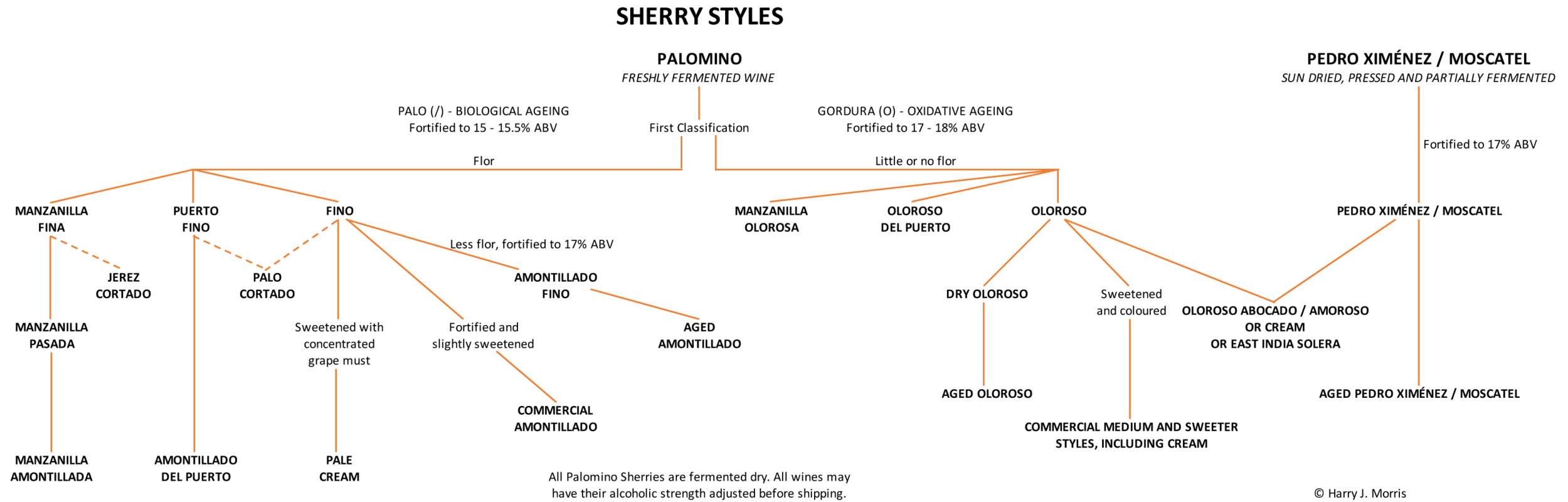

The low-acid, delicate base wine of 11-12.5% ABV is then separated from its lees, and the process of transformation begins. Two divergent paths of biological and oxidative ageing divide Sherry wines. At the conclusion of fermentation the wine is classified: each tank is either classified as palo and marked with a vertical slash, or as gordura and marked with a circle. Wines marked as palo are fortified to 15-15.5% ABV and are destined to become the more delicate Fino or Manzanilla styles. Wines marked as gordura are fortified to 17-18% ABV - a high level of alcohol that will not permit the growth of flor - and will become Oloroso Sherries. Neither wine is fortified directly with spirit, rather a gentler mixture of grape spirit and mature Sherry (mitad y mitad - “half and half”) is used to avoid shocking the young wine. Both sets of wines are transferred to neutral Sherry butts (600l used oak barrels). Fino and Manzanilla styles undergo biological ageing, whereas Oloroso Sherry undergoes oxidative ageing.

At the heart of the biological ageing process in Sherry is the film-forming yeast known as the flor del vino - the “flower of the wine”. While the normal yeasts responsible for alcoholic fermentation die as the wine’s sugar is wholly consumed, a specialised set of yeast species arrives to metabolise glycerin, alcohol, and volatile acids in the wine. Humid air carried on the Poniente wind, a moderate temperature between 60°-70° F, an absence of fermentable sugars, and a particular level of alcoholic strength (15-15.5% ABV) are prerequisites for the development of flor. As flor requires contact with oxygen, it forms a film on the surface of the wine that will protect the liquid from oxidation.

The flor grows vigorously in the spring and autumn months, forming a frothy white veil over the wine’s surface; in the heat and cold of the summer and winter it thins and turns grey. In the past, the growth of flor determined a particular wine’s future; it was a mysterious gift. Today, producers are much more aware of the process, and plan each wine’s future accordingly. Wines destined to undergo biological ageing are sourced from grapes grown in the finer albariza soils and are produced from the primera yema, whereas those destined for the oxidative ageing path of the Oloroso are more often sourced from barros (clay) soils and produced from the coarser segunda yema must. Once a wine has been marked to become Oloroso, its future is certain. Wines that develop under flor will enter an intermediary stage, the Sobretablas, for a period of six months to a year, during which the course of the wines’ evolution may be redirected. The wines, now kept in used 600 litre American oak butts, will be monitored and classified for a second time. The classifications are as follows:

- Palma: Fine, delicate Sherry in which the flor has flourished, protecting the wine from oxidation. Such wines will generally develop as Fino styles.

- Palma Cortada: A more robust Fino, which may eventually emerge as Amontillado.

- Palo Cortado: A rarity. Although flor is still present, the wine’s richness leads the cellar master to redirect the wine toward an oxidative ageing path. The wine will be fortified after Sobretablas to at least 17% ABV, destroying the veil of flor that protects it from oxygen.

- Raya: Despite its initial promise, flor growth is anaemic, or the protective yeast has died completely. The wine’s robust character is reinforced by further fortification to 17-18% ABV, and the wine emerges from Sobretablas as an Oloroso.

- Dos Rayas: The wine’s flor has disappeared, but its character is rough and coarse. Characterised by high levels of volatile acidity, these wines are either blended and sweetened for lower quality Sherry or removed from the Sherry-making process, often finding new life as Sherry vinegar.

After the second classification, the Sherry wines are ready to begin the long ageing process - DO regulations require a minimum three years of ageing prior to release. Rarely are Sherries marketed as vintage wines; most enter a system of fractional blending known as the solera, wherein new añada (vintage) wines enter an upper scale, or tier, of butts known as a criadera. Several descending criadera scales separate the young wines from the solera - the floor-level tier of butts from which the oldest wine is drawn and bottled. There may be as few as three or four criaderas, or as many as fourteen. For every litre of wine drawn from the solera, three must remain; thus the solera butts are only ever partially emptied (a process known as saca - “taking out”), and refreshed with wines from the first criadera. The first criadera is then refreshed with wines from the second criadera, and so forth. The operation of topping up, or refreshing, the space created in a scale is known as rocío (sprinkling), and the whole process of effecting the sacas and rocíos in a solera is called correr escalas (running the scales).

The Solera Criadera System

These movements of wine within the solera are known as trasiegos. In this manner a solera - derived from the Latin solum, or “floor” - will theoretically retain some small portion of its original wine, regardless of its age. Solera wines are often marked with the year the solera was started. The solera system is integral to biological ageing, as flor requires certain nutrients and oxygen to survive. The movement of wine from one butt to another provides oxygen; the addition of añada wines provides a constant influx of nutrients for the flor to prosper. While not necessary for oxidative ageing, many Oloroso wines are nonetheless aged in their own solera systems.

A cathedral-like Sherry bodega housing soleras - its huge space provides flor with the oxygen it needs to develop, it acts as an insulating chamber that regulates temperature and humidity, and its height is conducive to induced ventilation

Fino Sherry is a light, delicate, almond-toned style characterised by a high concentration of acetaldehydes, a salty tang, and a final alcohol content of 15-18%. As Fino matures, the flor might finally disappear. In this case, the Fino begins to age oxidatively, taking on a more robust, hazelnut character and slowly increasing in alcohol. If the loss of its protective veil is not ruinous and the wine is of good quality, it has the capacity to evolve into a Fino-Amontillado, finally becoming an Amontillado as its flavour, strength and colour deepen. The final alcohol content of Amontillado must be between 16% and 22%. The production of true Amontillado is a laborious process, and soleras devoted to the wine are expensive to maintain. The darker Oloroso, meaning “fragrant”, displays spicy, walnut tones and a smooth mouthfeel. Oloroso must range from 17% to 22% ABV. The rare Palo Cortado combines the rich body and colour of an Oloroso with the penetrating yet delicate bouquet of an Amontillado and is greatly prized by Sherry aficionados. These styles - Fino, Amontillado, Oloroso, and Palo Cortado - are generoso wines, totally dry in character.

The evolution of Sherry styles

Sanlúcar de Barrameda has its own classifications for generoso wines: Manzanilla Fina, Manzanilla Pasada, and Manzanilla Olorosa. Manzanilla Fina is similar in style to Fino, although the harvest occurs about a week earlier, and the resulting wines are lower in alcohol and fortified to a lower degree. In addition, Manzanilla wines are entered into - and moved through - the solera more quickly than a standard Fino. Manzanilla Pasada, like Fino-Amontillado wines, lose the protection of flor and begin to show some oxidative characteristics.

Although Sherry may be bottled as a dry generoso wine directly from the solera, it is more likely to be sweetened and blended before sale. The final blend is assembled on a small scale, often in a glass or test tube, and then applied proportionally to the wine at large. This process is known as the cabeceo. Base wines entered into the cabeceo must have a minimum ABV of 17.5%.

Several sweetening agents are available to the Sherry producer: dulce pasa, dulce de almíbar, and mistela produced from the must of “sunned” Moscatel or Pedro Ximénez grapes. Pedro Ximénez is preferred, but expensive. Dulce pasa - mistela produced from “sunned” Palomino - is the most common sweetening agent in modern Jérez. Dulce de almíbar, a blend of invert sugar and Fino, is rare. A Sherry house may also adjust the colour of the final wine with vino de color, a non-alcoholic concoction produced by a combination of boiled, reduced syrup and fresh must. If reduced to one third of its original volume, the syrup is called sancocho; if reduced to one fifth, the syrup is called arrope. Vino de color, naturally, also adds a level of sweetness to the wines. Generoso Liqueur wines produced by this blending process include Pale Cream, a lighter, fresher style blended from Fino wines; Cream, a darker, denser product of blended Oloroso; Dry, a paler style that actually contains a fair amount of sweetness; and Medium, a rich amber Sherry that may include Amontillado in the blend. Producers may legally label Medium Sherries with additional traditional terms, such as “Golden”, “Milk”, or “Brown”. Such terminology reinforces the long-standing importance of the British market, and the historic British control of the shipping houses and bodegas of Jérez. In the past, shippers relied heavily on almacenistas when configuring their blends. Almacenistas would purchase young wines, age them, and sell the wines to shippers at proper maturity. The role of almacenistas today is minor, and the term itself has been trademarked by Lustau.

Although the role of Moscatel and Pedro Ximénez in Sherry production is often supporting, wines produced solely from “sunned” grapes are occasionally sold as Vino Dulce Natural, or “naturally sweet wine”. The moniker is misleading, as the wines are fortified after a partial fermentation. Sugar content for both wines ranges from 180 to 500 grams per litre. Because Moscatel grapes are bigger than Pedro Ximénez grapes, the soleo process does not dry them to quite the same extent and the wines are slightly less sweet and concentrated as a result.

In 2000, the Consejo Regulador for Jérez created two new categories for Sherry Wines of Certified Age: VOS and VORS. VOS (Vinum Optimum Signatum, or “Very Old Sherry”) may be applied to solera wines with an average age of over 20 years. For every litre of VOS Sherry drawn from the solera, at least 20 litres must remain. VORS (Vinum Optimum Rare Signatum, or “Very Old Rare Sherry”) may be applied to solera wines with an average age of over 30 years. 30 litres must remain in the solera for every litre withdrawn. A tasting panel certifies all VOS and VORS wines, and only Amontillado, Oloroso, Palo Cortado, and Pedro Ximénez wines are authorised for consideration. Approval to use either label only applies to an individual lot of drawn wine, not the entire solera. The Consejo Regulador may certify an indication of age of either 12 or 15 years for use on a label; in such cases the certification applies to the entire solera, not just a particular lot of wine.

After working your way through all of that information, it's definitely time for a glass of Sherry!

Bodegas Valdespino, Inocente Fino Sherry

1. Bodegas Valdespino, Inocente Fino (15% ABV, £15.95 Lea & Sandeman)

Valdespino is possibly the oldest of the Sherry bodegas having been established in the thirteenth century by Don Alfonso Valdespino, one of twenty-four Christian knights who fought for King Alfonso X to liberate Jérez from the Moors. As a reward, the king granted him a parcel of vineyards in the area. The estate began selling wine as long ago as 1430, although the company in its current form wasn’t founded until 1875. Even in light of the substantial investment and modernisation by the new owner after being sold by the Valdespino family in 1999, this is a bodega that retains and champions many traditional production methods.

A number of factors make Valdespino’s Inocente a unique wine. It is now the last Fino to be fermented in wood, spending two to three months in 600l American oak butts, and it is fermented using native yeasts. Both of these features add degrees of character and complexity that far outweigh its price and the scale of its production. Inocente is also the only single vineyard Fino; its grapes are grown in the Pago Macharnudo vineyard, situated 5km to the north-west of Jérez at an altitude of 135m in an area renowned for the quality of its albariza soil.

Unusually for a Fino, Inocente’s solera has a high number of criaderas - ten rather than the norm of two or three, with 70 barrels to each scale - and the Sherry is about ten years when bottled.

Saline, yeasty, toasted almond nose; dry, salty and a touch sharp on the palate, with a creamy, nutty richness and a hint of green apple skin and lemon peel on the mid-palate. The long finish had a touch of volatility and overall this was fresh, complex and surprisingly vinous, especially for its age. Lovely.

Bodegas Hidalgo La Gitana, Pastrana Manzanilla Pasada

2. Bodegas Hidalgo La Gitana, Pastrana Manzanilla Pasada (15% ABV, £13.99 Majestic)

Hidalgo La Gitana is another venerable Sherry bodega, renowned for the quality of its Manzanillas. Founded back in 1792, it is today run by Javier Hidalgo, the sixth generation of his family to head the firm. Hidalgo is a rarity, being the last remaining bodega to produce and export its own unblended, single solera Sherries. Just as rare is Bodegas Hidalgo La Gitana's total reliance upon its own vineyards, 500 acres of Palomino Fino located in the prestigious albariza pagos ("crus") of Balbaína - the closest Jérez vineyard to the sea - and in Miraflores, the great Sanlúcar vineyard renowned for the pedigree of its wines.

Manzanilla is the Fino-style of wine unique to the coastal town of Sanlúcar de Barrameda. Here, the albariza soil has a higher salt content and this, along with the town’s proximity to the sea, is believed to give Manzanilla its distinctive briny character. The proximity of the ocean, and of the River Guadalquivir to the north of the town, makes Sanlúcar more humid than Jérez and this is beneficial to the growth of flor. However, as with a Fino Amontillado, over time the flor begins to thin resulting in the wine showing very slight signs of oxidation. This is then categorised as a Manzanilla Pasada (an “Aged Manzanilla”), a style pioneered by Hidalgo La Gitana. Pastrana is as unusual as the Inocente Fino tasted previously in that it is also a single vineyard Sherry. The Pastrana vineyard sits in Miraflores, to the southeast of Sanlúcar, on the crest of a hill overlooking the Atlantic where cooling ocean breezes allow the grapes to develop an uncommon intensity of flavour.

Hidalgo La Gitana is the only bodega to have 14 criaderas in its solera, and this Manzanilla spends around twelve years working its way up the scales. The nose displayed less of a fresh, saltwater character than a Fino and more of a savoury, Marmite character, along with a suggestion of exotic Indian spices. Similarly dry but richer than the Inocente, its palate displayed savoury Twiglet/yeast extract flavours with a hint of almond nuttiness. Not quite as long on the finish, but richer, more complex and more assertive.

Bodegas Rey Fernando de Castilla, Antique Fino

3. Bodegas Rey Fernando de Castilla, Antique Fino (17% ABV, £18.99/50cl Reserve Wines)

The modern firm of Rey Fernando de Castilla was founded by the scion of an aristocratic Jérez family as recently as the 1960s, initially concentrating upon brandy production before expanding its range of products to include a range of Sherries. Norwegian-born Jan Pattersen purchased Bodegas Rey Fernando de Castilla with a group of investors in 1999, immediately setting about raising its profile and creating a reputation for exceptional Sherries. He took full control of the company only a year later and he has been exploiting its potential ever since.

This wine was distinctive and somewhat old fashioned in style, having been aged for longer and fortified to a higher level (17% ABV) than most other Finos available today. This higher level of fortification was a commonplace until the 1980s, but since then the trend has been for lighter wines fortified to 15% ABV. The extra maturity provides richness and complexity; the additional alcohol helps to stabilise the wine, minimising the need for treatment and manipulation in the winery and giving it a longer shelf life once bottled.

Noticeably deeper gold than the other two Finos tasted. Pungent, salty, savoury and with a gentle yeastiness, somehow it vaguely reminded me of mature cheese. The palate was dry and fresh with a salty, preserved lemon tang, and a nutty, creamy richness; intense yet delicate at the same time. The finish had good length and a softly spiced, Twiglet flavour. A very individual wine.

Bodegas Rey Fernando de Castilla, Antique Amontillado

4. Bodegas Rey Fernando de Castilla, Antique Amontillado (19% ABV, £29.99/50cl Reserve Wines)

The Fino above is also used to feed the third criadera of the solera of this Amontillado where it is refortified to 18% ABV and where it matures with a degree of oxidation for a further 12 years.

A warm amber colour, with a nose of dried peel and raisin fruit balanced by salted, roasted nut aromas. Bone dry and disarmingly salty on the palate, rich with nutty, rancio flavours and the merest whisper of dried fruits and peel. Long, nutty and creamy on the complex, savoury finish. Excellent.

Gonzalez Byass, Del Duque Amontillado Muy Viejo

5. González Byass, Del Duque Amontillado Muy Viejo (£23.00/37.5cl Oddbins)

With support from his uncle, Manuel Mariá González purchased his bodega in 1835 to take advantage of Sherry’s popularity at the time. Originally imagined as a trading house, it soon began producing wine and, by 1844, vineyards had been purchased. As early as 1836, González had written to his English agent, Robert Blake Byass, mentioning that he was going to sell an exceptionally pale wine he had made. Soon after building his very successful La Constancia bodega, González formed a partnership with Byass to strengthen ties with the important United Kingdom market and, in 1863, the company’s named was changed to González Byass to reflect this union. The Byass family withdrew from the business in 1998, and the company is now owned and run by the fifth generation of the González family.

In honour of his uncle José Angel y Vargas, González created the Tío Pepe solera (“Tío” meaning uncle; ”Pepe” being the familiar version of José) in 1849. This brand was Spain’s first registered trademark and today it is one of the world’s best selling Finos, distributed to over 150 different countries. In 1835, the Duke of Medinaceli bought sixteen butts of Sherry and these formed the base of the current day Del Duque solera.

This wine began its life in the Tío Pepe solera and, after about four years when the flor had begun to fade, it was transferred to the Viña AB solera where it was aged oxidatively for another four years or so. Finally, it was put into the Del Duque solera and it remained there for a further 22 years in full contact with the air.

Deeper amber, almost a greenish, mahogany colour, and more viscous than the previous wine. A slightly sweeter and less saline/yeasty nose, offering nutty, coffee and caramel notes instead. Weightier and richer, dry, gently salty and nutty with a suggestion of dried fruit that quickly evolved into a very long, walnut and rancio flavoured savoury finish. Very fine.

Bodegas Rey Fernando de Castilla, Antique Oloroso

6. Bodegas Rey Fernando de Castilla, Antique Oloroso (20% ABV, £29.50/50cl Reserve Wines)

Similar in colour to the Del Duque, possibly a shade deeper amber. A sweeter, high-toned, almost Madeira-esque nose, completely lacking the yeasty, saline characters of a Fino or an Amontillado and instead offering aromas of tropical fruits such as mango and passionfruit. The palate was just off dry, with flavours of dried mango and walnut. Rich and balanced, with a lovely weight and a lingering finish.

Gonzalez Byass, Leonor Palo Cortado

7. González Byass, Leonor Palo Cortado (20% ABV, £14.75 Oddbins)

Although this was a similar colour to the Del Duque tasted earlier, it was not as viscous probably due to it being “only” twelve years old. A rich, tangy nose of dried mango and ginger ale, with a note of candied hazelnuts. Again off dry, edging more towards medium dry than the previous Oloroso. There was a touch of warmth to the palate as the alcohol was more noticeable than in any of the wines tasted thus far, although overall this was fresh, vibrant and very enjoyable.

Bodegas Hidalgo La Gitana, Wellington Palo Cortado 20 Years Old

8. Bodegas Hidalgo La Gitana, Wellington Palo Cortado 20 Years Old (17.5% ABV, £28/50cl Tanners Wine Merchants)

Fresher and lighter than the Leonor, despite being substantially older. A saline and walnut nose that was surprisingly delicate and coquettish. Dry, yet with an ephemeral suggestion of dried fruit richness that lingered hauntingly over the tangy, salty nuttiness of the palate. Very long and very lovely.

Bodegas Rey Fernando de Castilla, Antique Palo Cortado

9. Bodegas Rey Fernando de Castilla, Antique Palo Cortado (20% ABV, £35/50cl Corks Out)

This is produced with grapes from the older vines of a vineyard in the highly regarded Pago Balbaina, to the west of Jérez de la Frontera.

Deep amber in colour, with a bewitchingly beautiful nose. Massively complex, the aroma profile evolved in the glass from salty and nutty through to dried fruit and citrus peel and even a suggestion of cocoa or coffee. The palate echoed the nose, although its incredible complexity and length left me scrabbling for words. Wow!

Gonzalez Byass, Matusalem Oloroso Dulce Muy Viejo

10. González Byass, Matusalem Oloroso Dulce Muy Viejo (20.5% ABV, £19.99/37.5cl Waitrose)

González Byass is the largest Sherry producer and it owns 650ha of vineyards in the region, 95% of which are planted with Palomino and 5% are planted with Pedro Ximénez. It is the only winery to grow this variety in the region; most of the Pedro Ximénez used in Jerez is actually grown in the neighbouring D.O. of Montilla-Moriles where the drier climate is better suited to the soleo (sun drying) process.

Made from 75% Palomino and 25% Pedro Ximénez which are vinified and fortified individually before being blended and aged for thirty years in a solera. The combination of blending the two wines at such an early stage and a long ageing period meant that the final Sherry was beautifully harmonious, smooth and balanced without feeling cloying and without being dominated by the Pedro Ximénez.

Remarkably, the first bottle was corked. I suppose logically there’s no reason why a bottle sealed with a cork and plastic stopper is any more or less likely to harbour TCA than a bottle stoppered with a standard cork, but I’ve never previously encountered a corked example of a bottle sealed in this fashion.

Deep mahogany in colour, with a rich, sweet nose of dried dates and figs, molasses and darkly roasted coffee. Definitely sweet (130g/l of residual sugar), with a firm swipe of burnt sugar acidity across the palate. Dates, coffee, warm herbal and spiced notes from the Pedro Ximénez that have developed with age, along with a hint of nuttiness and lemon zest. Complex and well balanced with a very long finish - an archetypal sweetened Oloroso. Delicious.

Bodegas Valdespino, El Candado Pedro Ximenez

11. Bodegas Valdespino, El Candado Pedro Ximénez (17% ABV, £10.75/37.5cl Lea & Sandeman)

El Candado - “The Padlock” - is named in memory of the Valdespino ancestor who once locked up a barrel of this wine because he regarded it as being quite so remarkable. Hence the gimmicky packaging!

Deep mahogany coloured and viscous. Treacle toffee and dried fruit nose and similar on the palate. Very sweet (400g/l of residual sugar) but not hugely complex, I didn’t find this to be a particularly inspiring drink. It would be good added to arroz con leche (rice pudding) or to vanilla ice cream, and would work if served with chocolate desserts.

Bodegas Rey Fernando de Castilla, Antique Pedro Ximenez

12. Bodegas Rey Fernando de Castilla, Antique Pedro Ximénez (15% ABV, £30/50cl Corks Out)

Glass-stainingly dark, pretty much black in fact, and very viscous. More lifted on the nose than the El Candado with enticing aromas of treacle toffee, molasses, raisin, dried fig, coffee and more, plus a fresher fruit character peeking through. Monumentally sweet (500g/l of residual sugar) yet easier to drink than other Pedro Ximénez wines; the burn of so much sugar had mellowed over time and after 30 years in its solera it had developed an unctuous, velvety smooth texture. Treacly certainly, with a burnt sugar and liquorice complexity and a brightness from cold Darjeeling tea flavours and balanced acidity. Once again, my descriptive ability deserted me.

Bodegas Emilio Lustau, East India Solera Sherry

13. Bodegas Emilio Lustau, East India Solera (20% ABV, £21.99 Reserve Wines)

Lustau’s East India Solera is a sweetened Oloroso, its name referring to the East India Company, a British trading company founded in 1600 that transported cotton, silk, spices, tea, saltpetre, opium and many other commodities to and from the East Indies and China. At this time, barrels of fortified wines such as Sherry and Madeira were often utilised both as ballast and to serve the ships’ crews on their lengthy voyages to the East Indies and across the Atlantic to the Americas.

Sometime around the 1670s, it was noticed that wines returning from such round trips had actually improved, becoming smoother and more complex. This can be explained by the constant movement of the ships (causing more interaction with air and wood) and by the exposure of the wines to high temperatures (speeding up the maturation process). East India Sherry became very popular, although Lustau is now the only bodega honouring this tradition by recreating this historic style of wine. Made from 80% Oloroso and 20% Pedro Ximénez, the two components aged separately for around twelve years before being blended and aged for a further three years in a specific solera. To best replicate some of the conditions experienced by the well-travelled barrels of old, this East India Solera occupies the hottest and most humid area of the bodega.

Mahogany coloured, but not quite as deep as the Matusalem. Dates, raisins and walnuts on the nose, the Oloroso element provided a high-toned freshness. Sweet (130g/l of residual sugar), yet with a firm, balancing acidity. A faintly salty nuttiness and creaminess added complexity to the mid palate, although it lacked a little of the depth and complexity of the Matusalem. That being said, it was half the age of the Matusalem and even after only three years together the Oloroso and Pedro Ximénez had melded nicely without relinquishing any of their intrinsic qualities. A very impressive, and a very accessible, cream Sherry.